|

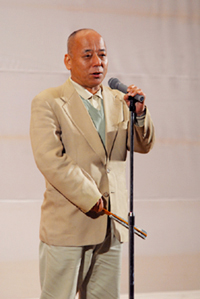

Akira Shigeyama performing the kyogen play Busu (”Sweet Poison”)

in a school. Even junior high school students who have grown up during the conto

(comic stories) and manzai (comedy) boom explode repeatedly with laughter during their

kyogen performances.

|

|

|

|

Kyogen

performer

Okura School Shigeyama Kyogen Kai

Akira Shigeyama

|

|

|

Kyogen drama: Like the widely loved tofu, it can be a premium dish or an ordinary meal depending on how it’s flavored.

The second-generation kyogen performer Sensaku Shigeyama once said,

”It’s good to perform kyogen that can be partaken of with pleasure in any environment,

like tofu.” These words have become the Shigeyama family motto, and their kyogen performances

have evolved hand in hand with Japans mass culture.

|

|

|

Akira Shigeyama says that ”Kyogen was the Yoshimoto Shinkigeki

[a popular contemporary stage comedy] of the Muromachi Period [1333-1573]”.

Kyogen was originally the performing art of farmers and townspeople and was

also the vernacular entertainment of the era, possessing contemporary theatrical

elements. For this reason traditional kyogen not only includes nonsense, jokes,

and criticism of the social system, but also incorporates elements of the erotic

and even of the grotesque. As it came under the patronage of the Tokugawa bakufu

(military government) during the Edo period (1603-1867), it was gradually

transformed into a higher-quality, more refined form of comedy.

According to Akira’s father, Sennojyo Shigeyama, his grandfather’s favorite

phrase was ”Kyogen is tofu.” During the Meiji (1868-1912) and Taisho (1912-1926)

periods kyogen was highly prestigious, but Akira’s grandfather did not care for

this sort of attitude and set out to give performances in whatever places he was

asked. Unlike in Edo (Tokyo), kyogen in the Kamigata (Kyoto/Osaka) region had

always existed as performances for the common people, and Akiras grandfather not

only continued this Kamigata tradition but developed it even further.

He described this concept of kyogen existing alongside ordinary people as ”tofu”.

His ”tofu kyogen” has been continued by subsequent generations, and the Shigeyama

family has raised it to the status of a valued philosophy.

One engagement by the Shigeyama family that typifies this philosophy is their

”School Kyogen.” This is a sort of ”delivery service” to schools that aims to

familiarize children with kyogen from a young age. This Shigeyama family initiative

began soon after the end of World War II. Sometimes the actors were not even paid for

their performances. They were satisfied if they received just a bowl of white rice to eat.

Despite such hardships, the Shigeyama family has continued to perform kyogen in schools

without a break for more than forty years following the war. Thanks to this effort, people

who saw kyogen when they were children continue to feel an affinity for it once they have

grown up and come to see performances. Akira identifies this as one of the foundations

underlying the current kyogen boom. Sennojyo, Akira, and Doji are passing on ”Tofu Kyogen”

in the present progressive tense.

One engagement by the Shigeyama family that typifies this philosophy is their

”School Kyogen.” This is a sort of ”delivery service” to schools that aims to

familiarize children with kyogen from a young age. This Shigeyama family initiative

began soon after the end of World War II. Sometimes the actors were not even paid for

their performances. They were satisfied if they received just a bowl of white rice to eat.

Despite such hardships, the Shigeyama family has continued to perform kyogen in schools

without a break for more than forty years following the war. Thanks to this effort, people

who saw kyogen when they were children continue to feel an affinity for it once they have

grown up and come to see performances. Akira identifies this as one of the foundations

underlying the current kyogen boom. Sennojyo, Akira, and Doji are passing on ”Tofu Kyogen”

in the present progressive tense.

Making a profit from stage performances such as the theater is

difficult in Western countries, and operations tend to fall into deficit.

Such thinking has led to the establishment of numerous cultural foundations,

and public support for stage performances has been actively developed. It may

arguably be said that survival thanks to public funding has become a standard

aspect of Western stage performance.

The path followed by the Shigeyama family is completely unilike this world

of dependence on public sector support. Their kyogen performances have continued

to survive for so long by existing in partnership with the townspeople as they

change from era to era. The wisdom of the strategy of making culture an everyday

affair so that it may continue is compressed into this history. There are very

many things to be learned from the Shigeyama family’s approach when considering

measures for cultural vitalization.

|

|

|

One scene from a program by three generations of

fathers and sons: Sennojyo, Akira, and Doji. Akira learned from Sennojyo,

who was himself the disciple of his own father, and from his grandfather,

the third-generation Sensaku (a living national treasure), to make the family

business of kyogen into something as everyday as tofu. Now he is passing on this

unbroken tradition to his son Doji’s generation.

|

|

|

Before the program comes a simple lecture to enable students who

have never seen kyogen before to enjoy it more fully. This lecture

itself is also packed with performances as a device to keep the students

from being bored. Even students who have gone into study mode as they read

the lecture notes are immediately drawn into the laughter when the program begins.

Before the program comes a simple lecture to enable students who

have never seen kyogen before to enjoy it more fully. This lecture

itself is also packed with performances as a device to keep the students

from being bored. Even students who have gone into study mode as they read

the lecture notes are immediately drawn into the laughter when the program begins.

Photographs courtesy of Kwansei Gakuin Junior High School

|

|